42: Jarama and Guadalajara

Description

After the Nationalist attack on Madrid was stopped, they shifted tactics and attempted to surround the capital with an attack from the south across the Jarama river and from the north near Guadalajara.

Listen

Maps

Sources

- The Battle for Spain by Antony Beevor

- Spain in Arms: A Military History of the Spanish Civil War 1936-1939 by E.R. Hooton

- The Spanish Civil War A Modern Tragedy by George R. Esenwein

- Spanish Civil War Tanks: The Proving Ground for Blitzkrieg by Steven J. Zaloga

- The Anarchist Collectives: Workers’s Self-management in the Spanish Revolution 1936-1939 Edited By Sam Dolgoff

- Patterns of Development and Nationalism: Basque and Catalan Nationalism before the Spanish Civil War by Juan Diez Medrano

- Blackshirts, Blueshirts, and the Spanish Civil War by John Newsinger

- Edge of Darkness: British ‘Front-Line’ Diplomacy in the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1937 by Tom Buchanan

- Franklin D. Roosevelt and Covert Aid to the Loyalists in the Spanish Civil War, 1936-39 by Dominic Tierney

- The Cult of the Spanish Civil War in East Germany by Arnold Krammer

- Fascism, Fascitization, and Developmentalism in Franco’s Dictatorship by Ismael Saz Campos

- Writing the Female Revolutionary Self: Deoloris Ibarruri and the Spanish Civil War by Kristine Byron

- A Spanish Genocide? Reflections on the Francoist Repression after the Spanish Civil War by Julius Ruiz

- The Spanish Civil War in the 21st Century: From Guernica to Human Rights by Peter N. Carroll

- The Revolutionary Spirit: Hannah Arendt and the Anarchists of the Spanish Civil War by Joel Olson

- Seventy Years On: Historians and Repression During and After the Spanish Civil War by Julius Ruiz

- Fascist Italy’s Military Involvement in the Spanish Civil War by Brian R. Sullivan

- The Spanish Civil War: Lessons Learned and Not Learned by the Great Powers by James S. Corum

- Truth and Myth in History: An Example from the Spanish Civil War by John Corbin

- ‘Our Red Soldiers’: The Nationalist Army’s Management of its Left-Wing Conscripts in the Spanish Civil War, 1936-39 by James Matthews

- Multinational Naval Cooperation in the Spanish Civil War, 1936 by Willard C. Frank Jr.

- ‘Work and Don’t Lose Hope’: Republican Forced Labour Camps During the Spanish Civil War by Julius Ruiz

- The Spanish Civil War, 1936-2003: The Return of Republican Memory by Helen Graham

- Soviet Armor in Spain: Aid Mission to Republicans Tested Doctrine and Equipment by Colonel Antonia J. Candil, Spanish Army

- The Soviet Cinematic Offensive in the Spanish Civil War by Daniel Kowalsky

- Soviet Tank Operations in the Spanish Civil War by Steven J. Zaloga

- The Spanish Military and the Tank, 1909-1939 by Jose Vicente Herrero Perez

- The Theory and Practice of Armored Warfare in Spain October 1936-February 1937 by Dr. John L. S. Daley

Transcript

Hello everyone and welcome to History of the Second World War Episode 42 - The Spanish Civil War Pt. 7 - Jarama and Guadalajara. This week a big thank you goes out to Joseph for their support on Patreon, where they get access to ad free versions of all of the podcast’s episodes plus special Patreon only episodes released once a month. If that sounds interesting to you head on over to historyofthesecondworldwar.com/members to find out more information. Last episode we discussed some of the transitions that occurred within the Nationalist leadership as it tried to transition from a group executing a coup into one capable of forming a coherent government and staging a civil war. Today we will look at another important transition that would occur as the Civil War began to intensify and this was the transition of the Republican military forces from a loose collection of militias to something that looked much more like a typical military. The Republic would be at a military disadvantage when the fighting began, however just in terms of numbers the disparity would not last long. However, this disparity would return and would grow over time, especially as the foreign aid provided to the Nationalists began to vastly outstrip, both in quality and quantity that which was provided to the Republic. This growing disparity would only come in the later years of the war, and in the autumn of 1936 a more immediate problem had to be solved and the Republican leaders would make it a priority to transition their forces into more traditional military formations. AS they would try to complete this change the Nationalist attacks around Madrid would continue, two of which we will discuss today, the Jarama and Guadalajara offensives. These attacks in early 1937 would make it clear that a Nationalist military victory, should it occur, would be far from easy. It would also be the point where much of the qualitative advantage that had been enjoyed by the Nationalists would dissipate, as the Army of Africa would lose many of its most skilled and experienced units. For this episode I have put two maps up on the website for each of the battles we will be discussing today, which might be very useful to check out.

In October 1936 the first and important step away from the militia units that had dominated the Republican military efforts up to that point would be taken and the Popular Army was officially created. This move was initiated with the supporting of the remaining officers of the War Ministry, many of the political leaders, and the Communist party. They believed above all that the only way to effectively defend the Republic was through this action. This idea was reinforced by the incredibly poor performance of the militias when met with the early offensives of the Army of Africa and other Nationalist forces as they moved on Madrid. An important point to remember is that this decision, made in October, was before the battle of Madrid started, and up to that point, after the initial successes in meeting the coup attempt, the Republican had known little but defeat during the fighting. These failures would be the reason for the final push back towards a more formal military structure. There were also hopes among Communist leaders that such a move would help to solidify their power and reduce the powers of the militias controlled by their political opponents, specifically the anarchist militias. Speaking of those anarchist militias, they were not really big on the idea of militarizing the militias. For the anarchists the traditional state military was seen as the antithesis of their beliefs, and so when they were being folded into the new army they were at the very least greatly concerned. However, these ideological concerns were met with a litany of reasons for why the militia system was incapable of what was being asked of it. Most of those within the militia units had no formal military training, and they were led by elected officers who were often trade union and community leaders, not soldiers. There was resistance to orders and little coordination between units. Even if many anarchists might recognize these concerns, there would still be resistance to the militarization that was taking place. It did not hope that the people who had been willing to drop everything and join the militias were some of the most dedicated to their beliefs, and often those beliefs conflict with the militarization process. Regardless of possible qualms with what was happening the militia units would be slowly militarized, with columns turned into battalions and brigades in late 1936, with larger units organized in 1937. This would split the anarchist militia members in the same way that the larger collaborationist argument would split the movement during the Civil War.

Along with a reorganization during the winter of 1936 and 1937 three additional classes of conscripts would be called up. These were the 1933-1935 classes, so those 19 to 21 years of age. There were also some volunteers that continued to trickle in, with some young men motivated to enlist for the food if nothing else, as there were serious food shortages in many areas of Republican Spain. All these sources combined allowed for the number of men in the Republican military to greatly expand, and by the spring of 1937 they were able to must about 320,000 men in total. These were split into three different groups the first being the 130,000 in central and southern zones which were under the command of the government from Valencia, 100,000 in the northern enclave which were under the command of local leaders, and 30,000 in Aragon in the northeast which were under the control of the Catalonian government. Within these armies there were two primary problems, at least which it came to the men who led them: first up was the fact that many of the same problems that would plague the Nationalist armies would also effect the Republicans. This meant that their officers were often hesitant and far more used to the bureaucracy of peace than the action of war. There also was simply not enough of them, especially when it came to staff officers who were so important in terms of organization. This shortage of staff officers, and a general lack of imagination among many of the commanding officers, resulting in several very straight forward operations. Even in the cases where they were able to achieve tactical success, it often proved impossible for any operational success to be found, which was absolutely not a problem unique to the Republican forces, the Nationalists and many of the armies during the First World War had similar problems. This meant that even the successful Republican attacks would often transition into battle of attrition very quickly, with the Nationalists able to contain the advances. Many of these attacks were planned by, at the time, Colonel Vicente Roja, who would be one of the most influential Republican military leaders, and would later be chief of the General Staff. One of the operations under consideration was an attack near the Jarama Valley, but the Nationalists would attack in the same area first.

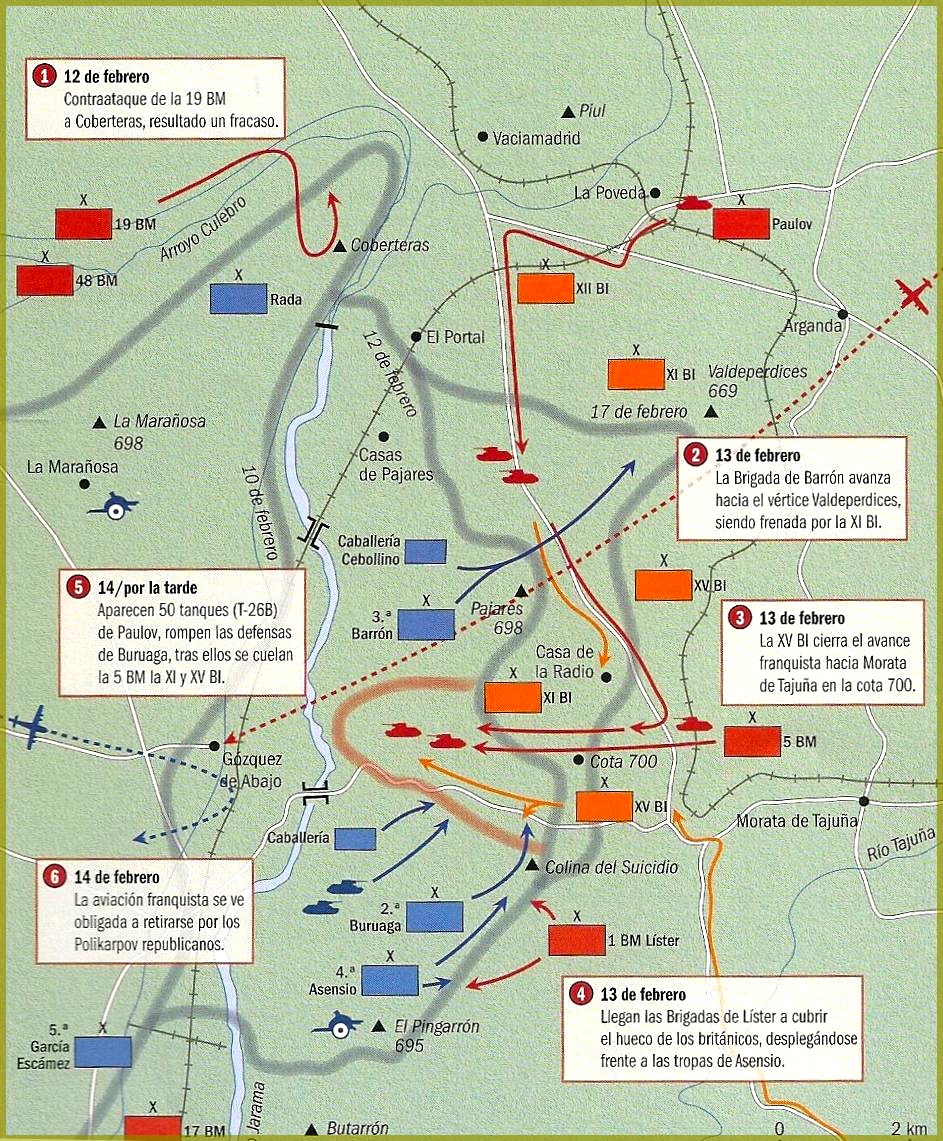

This attack would be launched in the continuing effort to cut off Madrid, which even after the efforts of the Nationalist forces in late 1936 and the first week of 1937, was still far from surrounded. The plan was to launch an attack to the southeast of the city over the Jarama river with the objective of cutting the highway the led to Valencia, where the Republican government had fled during the early stages of the attack on Madrid. The larger plan was then to continue the advance and to meet an attack coming from the north, with the Jarama effort joined by an attack by the Italian Volunteer Corps which would be launched to the north of the city in the hopes of meeting at Alcala de Henares. However, there were delays in preparing for the Guadalajara attack in the north, with some pretty poor January weather playing a part, which prompted Franco to decide to launch the Jarama offensive by itself. The troops allocated for the attack would once again be under the command of General Verela with around 25,000 men, although only 5 would be directly taking part in the attack. The majority of these troops were from Morocco, which gave the Nationalist officers additional confidence in their success. They would be supported by German machine guns, tanks, and artillery. The plan called for an attack that would reach the river, then cross it to establish some beat heads, then advance on the high ground near the Valencia Highway, and then the final push towards Alcala.

As I mentioned just a bit ago, the Republicans were also planning for an attack in these area. The Soviet advisors that had been sent to Spain had been suggesting such an attack, and the Republican General Staff had finally agreed. The troops had even been moved into the area, with around 50 battalion already in place, which meant that when the attack began there was rough parity between the forces involved. The initial jumping off date for the Nationalists had been January 24th, but starting on that day there would be rain for ten consecutive days. This turned the area into a muddy mess, and when the rain finally ended on February 4th it soon became apparent to the Republicans that the Nationalists were going to launch an attack. The Republican leaders quickly cancelled any preparations for the own offensive, which was planned to start in the near future, and instead had all units prepare to meet the attack. While they knew it was coming, they did not know exactly where the focal point would be. On the Nationalist side, after the rain had ended, the attack was rescheduled for February 6th. On that date there was some initial success, and the Republican forces would be thrown back in confusion. By the 8th they would have reached the river in many areas and had consolidated control over most of the West Bank. However, they were unable to ford the river due to all the recent rain and so they were delayed. This gave the Republican forces a break, but there was still some concern with the Republican leadership that the current attack was simply a feint and diversion, either of another attack elsewhere on the front, or as a precursor for the current attack to switch directions and begin to move towards Madrid, this made the Republican leaders hesitant to commit further resources.

The first Nationalist troops across the river would make the jump at the Pindoque rail bridge. Varela would order a night attack against the bridge in the hope that this would catch the Republican defenders by surprise. This was achieve with a small force crossing the river and killing several sentries with knives These sentries were actually Frenchmen who were members of the XIV International Brigade, and their death allowed the Nationalist units to capture and begin to move men and equipment across the bridge. This included antitank guns which were brought across the bridge in time to deal with a small group of tanks used in a Republican counterattack. There was heavy fire thrown at the bridge by both the XII International Brigade and Republican artillery, which slowed the advance of the brigade that had made the crossing. This could not prevent the establishment of a stable bridgehead, and while this represented a success for the Nationalists the entire attack had been at the cost of 720 casualties. When the advance was resumed the next day it would run into two major problems. The first was that the two International Brigades that were in their path would put up some serious resistance, and the Republican artillery would continue to shell the bridge and surrounding areas, making the movement of men and supplies to the forward areas quite difficult. Another crossing was also made at dawn and just hours after the events at Pindoque, this crossing was at San Martinde Le Vega. In both of these areas progress was made, but the defenders, both International and Spanish, would be able to hold onto a few important geographical features. Attacks continued during February 13th, pushing forward until eventually troops from the Pindoque bridgehead were able to reach the Valencia highway. By this point some of the defenders were beginning to collapse, but Varela felt that the troops were too far forward and exposed to a possible flank attack and he ordered a halt to their advance. What they did not know was that they had pushed the Republican defenders into a state of complete disorganization, but the Nationalist overestimation of Republican forces called for caution. Varela then requested further reinforcements before any further attacks were ordered. The pause provided time for Republican forces to be brought into the area and a counter attack to be launched, including 50 of the Russian T-26 tanks that had made their way to Spain. The counterattack was not able to erase all of the Nationalist gains, but it did seriously reduce the ability of the Nationalist forces to attempt another attack.

The attack on the Jarama was important for many reasons, not the least of which was that it represented a clear end to Nationalist supremacy in two key areas. The first was in the air, because during the offensive the Republican air forces were able to obtain some level of control of the air through the use of their Russian aircraft and pilots. The Russian planes were better, and there were also more of them, with the Nationalists had problems getting more fighters from the Italians who were at this point their primary source. The larger change was within the Nationalist army. They had entered the war with a notable advantage in terms of experience within their ranks, but on the Jarama many thousands of those troops had been sacrificed. Some historians have equated it to what happened to the British forces in Ypres in late 1914, with the attack at Jarama sacrificing simply too many of the professional soldiers that had come across from Africa in the early days of the Civil War, which was a resource that the Nationalists could not replace either easily or quickly. The effective resistance of the Republican troops was also very different than some of the earlier attacks in the autumn of 1936, and the Nationalist leaders, Franco among them, simply could not adapt fast enough to this new reality. There was heavily criticism of the Nationalist commanders for their actions during the Jarama attacks, and especially of their decision to continue such attacks even as the costs mounted. This criticism primarily fell on General Orgaz, Varela’s command, and Orgaz would be removed, although he would be reassigned to command the mobilization and training of officers for the Nationalist army. The objective of the offensive was also never achieved, the Valencia road remained open. There were discussions about resuming the attack when the Italians attacked near Guadalajara in early March, but it was decided that the troops near the Jarama were simply not capable of mounting another efforts.

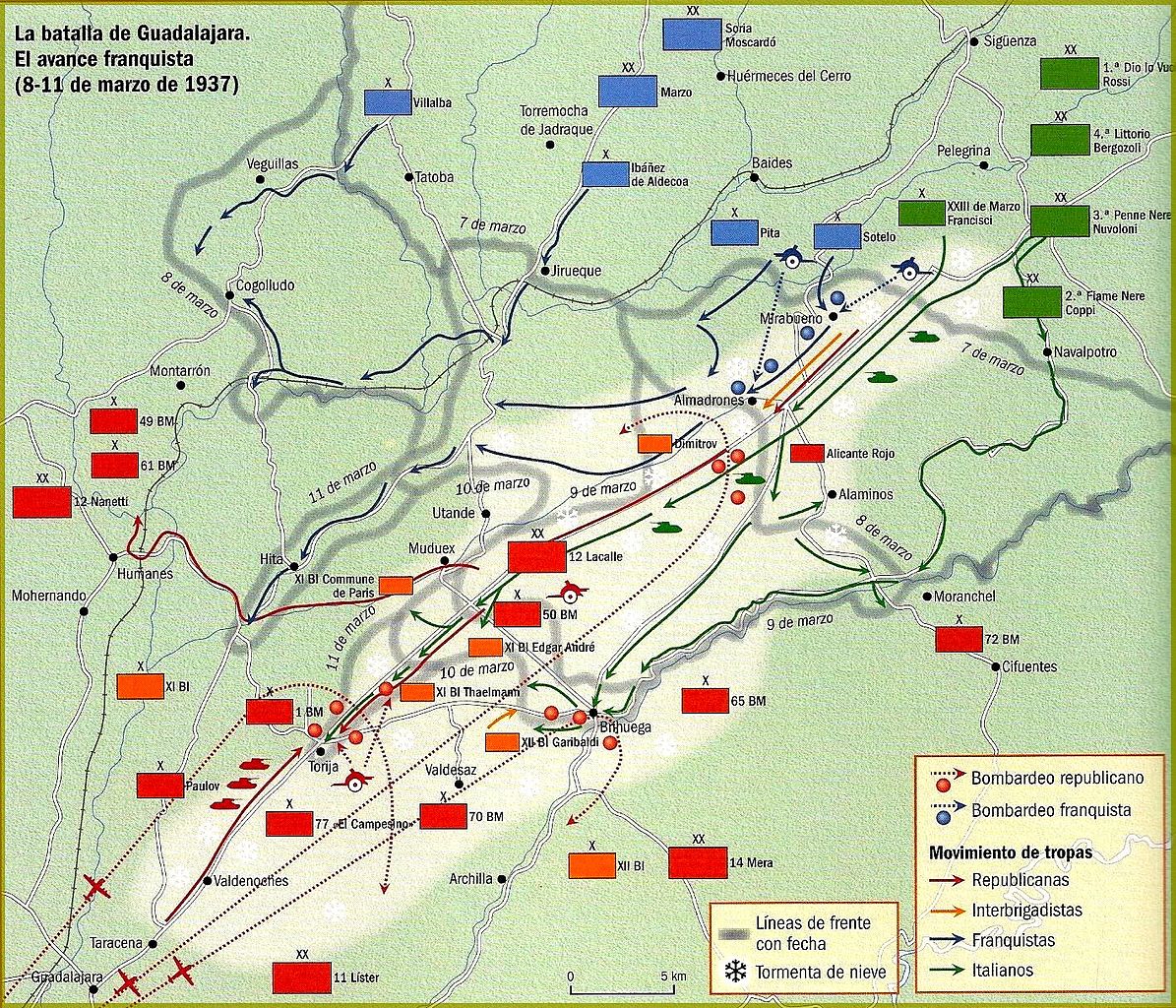

Even with the failure of the attack at the Jarama, the planned attacking the north would still be scheduled to occur, even though it would only be able to do so after a delay. Franco still wanted to capture and isolate the capital, and there was also pressure coming from the Italians to have their troops, the Corpo Truppe Volontair, or CTV, used in an attack. The CTV was commanded by Major General Mario Roatta and was primarily made up of Italians that had been a part of the fascist blackshirt militia who had first seen experience in Ethiopia. Mussolini wanted the CTV used for such an attack as a way of boosting Italian military prestige, and so supplies and men were moved into the area for the attack during the early months of 1937. Roatta would eventually have over 31,000 men although not all of them would take part in the attack, and those that did would be joined by many Spanish units as well. Interestingly, there was also a huge stockpile of chemical weapons moved into place, including mustard, phosgene, and less lethal substances like teat gas. These would not end up being used, but they were in Spain to be used by Italian forces and apparently Mussolini was an advocate for them. As mentioned earlier the initial plan had been to launch the Italian attack simultaneously with the one on the Jarama, but due to Italian delays the attack in the south would occur unsupported. By the time that the CTV was ready, the attacks in the south had ended and so the nothern attack would be the ones going forward unsupported in March. This did not greatly deter either Franco or Roatta from launching the attack, with the vague hope that once the northern troops got rolling attacks in the south would resume. The Italian plans were to attack towards Guadalajara from the northwest, they would move along the road that ran into the town, using the Blackshirt troops as a spearhead for the offensive. The final objective of the attack, Alcala, was 75 kilometers away, which is where they planned to meet up with Varela’s troops moving from the south. Apparently when this planning was occurring Roatta and the other Italian leaders had very little idea on what they were attacking into, and they possessed very few maps of the area. This prevented proper detailed planning from occurring, which when combined with some of the poor decisions made during the process would create real issues. For example, the weather was predicted to be quite poor on the opening day of the attack, March 4th, and it was likely there would be rain combined with the cold weather. However, this was not seen as as huge problem because Roatta believed that the attack would be quick, to the point where he even ordered the field kitchens to be left behind. After the Italian plans were shown toFranco, the Nationalist leader was concerned that the Italians were leaving themselves far too exposed on their left flank, but Roatta was very confident and did not heed these concerns.

When the Italian troops prepared for the attack on the night of March 7th, the weather was abysmal with snow, sleet, rain, and cold temperatures making everything very uncomfortable. In some areas visibility was down to 100 meters but that did not prevent the advance from beginning, with the Italian troops on the left and Spanish troops on the right. Despite these issues, progress was made, and while some sectors faired better than others, a bit under 20 kilometers was achieved at the furthest point. The lack of visibility, beyond just making things difficult, also caused some officers to favor a more cautious approach, which slowed the advance. On the next day there would be great progress made on the far left of the attack, mostly thanks to the efforts of the motorized Italian troops who were able to use some armored cars to quickly pass through the Republican lines. However, the poor weather continued which caused the entire operation to slow down. Some Republican reinforcements had arrived on March 8th, but at least initially these were small in number. After the large jumps of March 7th and 8th the Italian left found that any further progress would be hard going. One of the largest problems was logistical, with the road network disrupted by the battle which caused a huge problem was supplies and men tried to continue toward the front. This, along the a stiffening of Republican defenses and the growing exhaustion of the attacking forces meant that over the next several days, even though more attacks were launched, they barely crawled forward. In an attempt to restart the advance additional air resources were brought in, with Italian and German bombers being utilized in greater numbers, this would include the first combat flights of the German He-111. In addition to more air support more Italian troops were also added to the front and they would initially do quite well, on March 11th they would be able to move into a capture Torija. However, on the left and the right of this advance far less progress was made, which left those that had advanced the furthest in a dangerously exposed salient. The troops on the left were able to take the town of Brihuega, which was one of the core objectives, but they were far behind schedule and running out of men and energy. By the end of March 11th the Italian forces were in a rough spot, they had failed in their attempts to decisively break through the Republican front. Four days of fighting in cold damp weather was just adding to the normal exhaustion experienced by troops in combat. When they asked Franco about the status of further efforts on the Jarama, to try and make further Italian success more likely Franco said that they would resume the next day. These attacks would not occur, and instead a Republican counter attack would be launched to try and recapture the territory lost to the Italian advance.

Even before they began their counterattack, Republican strength was rapidly growing, both on the ground, with a total of 35,000 men, and also in the air. Much like at Jarama the fighters provided by the Russians were able to control the skies and launch air attacks against Italian and Nationalist formations. It was challenging for the Nationalist forces to interdict these attacks due to the weather. The Republicans also had the advantage of flying out of larger airfields, specifically the one at Albacete with its paved runway. The Nationalist air facilities in the air paled in comparison, and many of the Nationalist airfields with dirt runways had become almost unusable. With these resources the Republicans planned to counter attack, and the plan was very simple, troops would be concentrated onto two axes, the first one would be given most of the available tanks and it would move up the Saragossa road. The second would cross the Tajuna river with the goal of retaking Brihuega. On the other side of the line the Italians were also preparing to attack, which was a decision made only after several discussions between Roatta, Mola, and Franco. Roatta was hesitant to continue, and Mussolini was agitating for the CTV to be moved to another part of the front, hopefully one where great offensives were more likely. Mussolini was concerned that events around Madrid had simply reached a stalemate, and he had sent the CTV to Spain for great sweeping victories, not to get embroiled in battles of attrition. Roatta was eventually convinced to resume the attack. He had been concerned about the possibility of a counter attack, but with the possible resumption of the attack in the very near future the Italian units had not spent enough time preparing their defenses, which would make them vulnerable when the Republican attack was launched. The counterattck would begin on March 12, and would continue at varying levels of intensity for the next 10 days. They would, for the most part, slowly push forward with both Soviet tanks and aircraft used to try and keep some momentum going. After the first attack on the 12th the next major effort would be on the 18th. On that day the weather was against the Republicans, with heavy cloud cover in the morning. Hours later when the sky cleared the Soviet tanks under the command of Colonel Pavlov would move forward. The Italians found it very difficult to keep the situation under control, with one of the reasons being that this attack had the fortune of attacking while Roatta was away from his command post, having flown to Salamanca for discussions with Franco. In his absence a withdrawal was ordered, which resulted in the Republican recapture of Brihuega. Roatta was informed of this retreat while in a meeting with Franco.

The withdrawal of the Italians caught the Republicans unable to truly follow up before a new line was established. Further attacks were launched up to March 22nd, but they were unable to replicate the earlier successes. In the end the line settled down with about half of the territory in Nationalist hands at their high water point back in the hands of the Republicans. For a small advance, without any major objectives captured, the Italians had lost just under 3,000 men. However, the effects on the CTV went far beyond just numbers, their morale was shattered. The situation was bad enough that Franco discussed disbanding the CTV altogether and dispersing all of its men and equipment to other units. Instead Roatta was removed from command, and the CTV was put through a large reorganization with General Ettoro Bastico arriving to take command. For the Republicans Guadalajara would be publicized as a great victory, a boost to morale. In terms of the course of the war the two battles of Jarama and Guadalajara had one further effect, they would mark the point where Franco’s focus on quickly capturing Madrid was broken, forcing him to accept that it would be a longer term project and that Nationalist efforts were better used elsewhere. Next episode we will discuss the northern Republican enclave, which would become that elsewhere.